It is difficult to fully comprehend the changes that took place around the time John Milton wrote his epic of how Adam and Eve where extirpated from the Garden of Eden - Paradise - and how it was lost to them. In fact, most of the changes in Milton's life took place some time before he but his epic into words. As a revolutionary puritan, he witnessed some of the most intense political changes in the English landscape at the time, and landed on the wrong side of the Restoration. The wigs and the torys where vying for power, and to modern eyes, ears and cognitive apparati, it often proves somewhat of an acrobatic exercise - not to mention an excursion of imagination and empathy - to fully take in how much religion played into every aspect of not just ordinary life, but politics. How are we to understand the Christian message, the role of the Holy Spirit, the overarching plan of God the Father, in these times where the very conception of what it means to be a human has changed? Milton and his contemporaries pondered. And what is the best direction forward for the Island Nation of England?

England was by the dawn of the 18th century one of the wealthiest, most successful and powerful nations on the planet, having harvested the goods of expansive colonial politics abroad, and complex parliamentary and monarchical mechanisms at home. London was by some estimates, the largest city on the planet by far, the first city to eventually reach the 1 million-people bench-mark. London, as a gargantuan trade-hub, entrepreneurial haven and seedbed of technological growth, was also, and perhaps most importantly, a marketplace of ideas.

Milton wrote Paradise Lost at a time when his politics of radical reform had gone awry, his eyesight lost, and his cultural influence fading. He was not wholly put out of favor, but it is clear that he neither physically nor mentally was in the best place of his life. Yet out of this state "myself, almost despising, happily, I think on thee" to quote Shakespeare's sonnet nr. 29. where we can think of Milton as contemplating his Muse, the one he implores to sing a song of epic proportions on the topic of how Paradise was lost, and we humans became what we are. It is almost as if Milton is showing us through his own state, how it is that - despite our best efforts - we end up in conflict, misery, blindness and destitution. Indeed, it is not just "almost". Part of the entire point of Paradise Lost is not just to gift a beautiful poem to the world, one in the renaissance tradition begun with Shakespeare & Co. in which ancient sources are heavily drawn upon, but indeed to "justify the ways of God to Men". This is reminiscent of Milton’s contemporary Alexander Pope, who writes in the classical way with a strict form, rarely surpassed, yet later criticized, in which Pope in many ways accounts for, explains etc. the Nature of Man in his Essay on Man. He satirizes over the human condition, but fully in line with the renaissance humanism, places humans at the center of their (our) own investigation, and as responsible for further investigating both ourselves and the universe to which we are a part. "Know then thyself / the proper study of mankind is man / Placed on this isthmus of a middle state / a being darkly wise and rudely great / he hangs in between / in doubt to act or rest / in doubt to deem himself a god or a beast / in doubt his mind or body to prefer / born but to die / and reasoning but to err" yet also, fully in line with the ancient concept of hubris dampens human arrogance by showing us how we, as both subjects and objects of our own thinking, easily falls pray to our own search for ever more power, understanding and influence thorough the collapse of our projects.

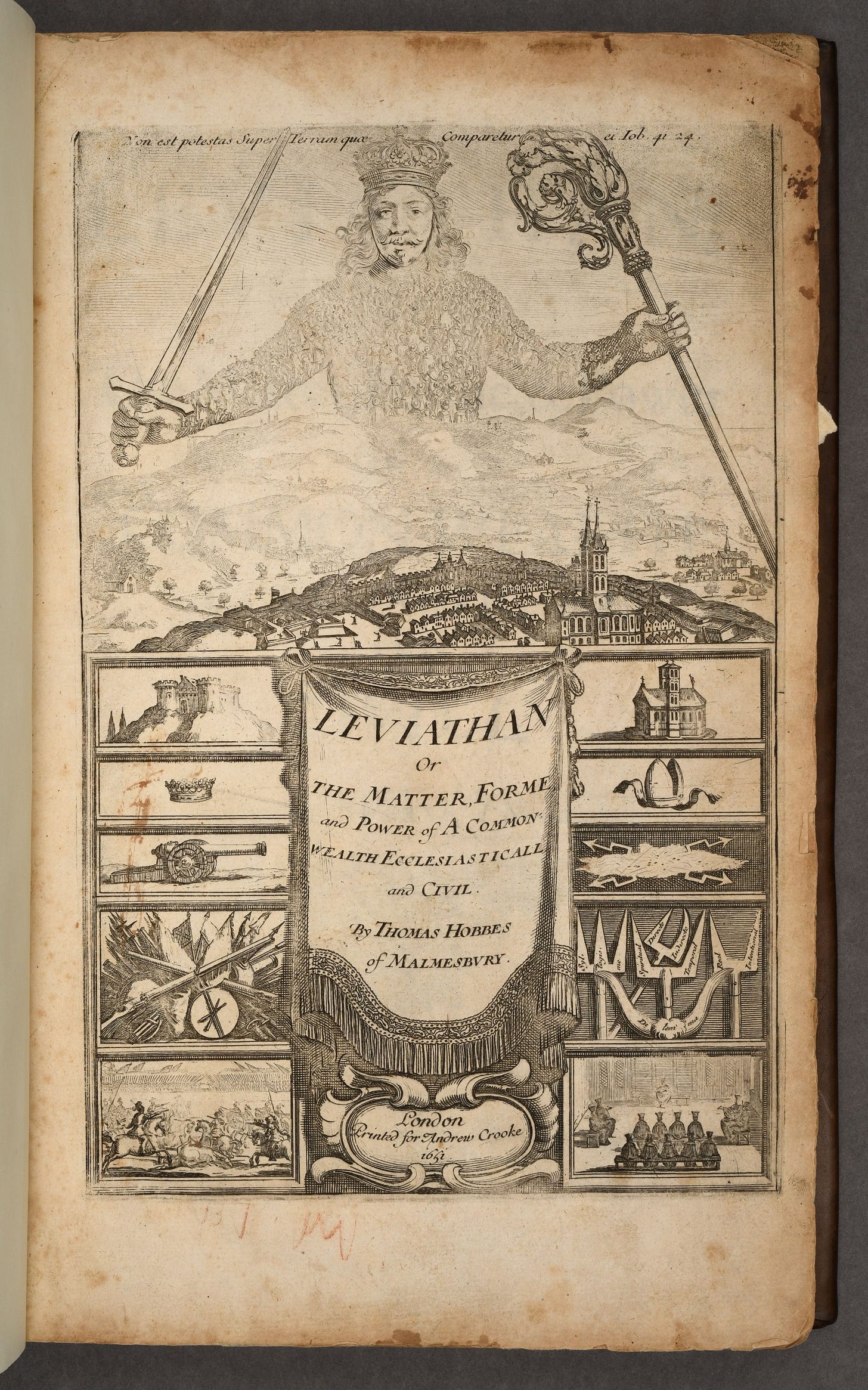

As I began this essay, these were not just radical times in terms of political, religious and technological changes, but in ideas. The burgeoning empirical sciences were recently introduced, and with them, ideas of how the world works, what it was made of and what us humans are made of, our role and epistemological reach, where emerging that were completely unprecedented in human history. Locke had presented his idea of humans as tabula rasa, blank slates for the senses to empress upon, and with it, an empiricist idea of how humans worked. Francis Bacon had presented his own, radical views on how we should approach nature, and with an imperialist flourish, suggested that we should penetrate nature to her depth with our new methods. Thomas Hobbes, known more for his political philosophy of the Sovereign as a peacekeeping mechanism, is also known for his idea of humans as fundamentally material entities. "What are the muscles if not strings ... what is the heart but one large string?" he contemplated. He also, in a mode reminding us of the aforementioned Locke-thesis of tabula rasa, presented a thesis of thinking as "reckoning" that is, in stead of a spiritual abstract phenomenon, thinking (i.e. mental activity) is "calculating". For Hobbes, thinking is a form of mechanical activity; an understandable process, in essence, wholly explicable in material terms.

And this is where Adam - Locke, Pope, Milton, Bacon, Hobbes - asks the angel Raphael what he is. In Book 5., lines 469-543, Raphael provides a monologue in which he accounts for angels, their nature, being and role in creation. Yet, this is not all he does; as he accounts for his own angelic being, he also explains how Adam works. In fact, not just Adam; Raphael proceeds to account for the metaphysics underlying all beings. It is as if he is saying "Oh Adam, my dear human, I see how you do not see how everything fits together, so let me provide you with a background from the Angelic point of view.

Everything comes ultimately from God, the source and wellspring of all that is; Creation. Everything is part of creation, and intermingled with it. "All things proceed, and up to him return" Here Raphael seems to imply that nothing is really lost even if it were to change shape, as even when they seem lost the somehow return to him (God). Much like the liturgical "ashes to ashes, dust to dust". We are created in His image (Imago Dei) yet we are also made literally from the "dirt". The way to interpret this is that we are created of/with/in the same stuff as the rest of the world, we are literally (yes, not just figuratively) part of the world. The stuff, dust, dirt, ashes is here simply the name for "matter" the very extended substance (as the french philosopher René Descartes called it) that could be investigated via the new sciences. Matter is not "simple" or "crude" yet complex and multifaceted. Everything we see, hear, smell and touch is made of it, and as I mentioned, everything "proceeds and returns" in the same cycle. Later, the science of the intricate interconnectedness of living organism would be called "ecology". Which interestingly enough comes from "eco" from the ancient Greek word for "house" and "logos" (word, meaning, understanding etc.)

"Endued with various forms, various degrees

Of substance, and, in things that live, of life"

As we can see here, Raphael is mentioning living things, but that is only after he mentions "of substance" which in the philosophy of the time, is simply a matter of referring to entities, to physically recognizable shapes. Various forms there exists, and various living things, are also endued with form. They are both alike in the dignity of form, the living and the non-living. But what about humans and angels then?

"But more refined, more spiritous, and pure,

As nearer to him placed, or nearer tending"

The angelic beings being spiritual are more "elevated" than humans, since they are "nearer to him placed, or nearer tending." The latter can mean, "closer to his nature, in behavior, mode" etc.

"Each in their several active spheres assigned,

Till body up to spirit work, in bounds

Proportioned to each kind"

Active spheres can mean, to continue that line of argument "their own mode of life, their own behavioural tendencies" or to get a little biological "their own evolutionary niche." In evolutionary biology, evolutionary niche designates the adaptive environment of creatures that have taken advantage of certain features of their environment, to which they have continued to adapt. This can also mean changes in the very body-structure of the organism. Bats have developed echo-location in order to by sound locate their pray at night, which turns into the bats "assigned sphere." The tortoise was an ancient reptile whose scales fused and made a permanent defense system for the creature, allowing it to live across various parts of the world, in water and on land. One might say that the very shell of the turtle is its evolutionary niche, its "sphere assigned". Some animals are highly adapted, which means that they are very tuned indeed to the place at which they found a niche. Dung beetles who survive on excrements and have adapted to a life of sophisticated poop-handling; beetles that live solely in certain forms of tree-bark; leeches that live in water and suck the blood of larger animals; butterflies which can only harvest nectar from certain flowers at night in certain parts of the year etc. When two life-forms adapt to each other like this it is called co-evolution.They are each others "spheres assigned." In Milton's world though, there is a hierarchy, a chain, a ladder of beings. And the higher ones a more "spiritual". But how? Not by consisting of another kind of "stuff" but in another degree!

So from the root

Springs lighter the green stalk, from thence the leaves

More airy, last the bright consummate flower

Spirits odorous breathes: flowers and their fruit

There is a degree in being, not just in Being that is (Being with a big B, is All that is, That things are, that there is something rather than nothing, that things have Being means philosophically that they have existence) but in beings. So withing Being and withing beings, there are degrees. Within a single being, say, a tree, there are also degrees of "spirit" or "soul." As Raphael explains, the root is the most basic, it is in a sense fundamental, as it provides nutrients and stability, yet it is not the most elevated. In the case of the tree, it is also literally at the bottom part. As one goes higher in the arboreal being, one encounters different shapes and forms of expression. The higher up one comes in the young tree, the lighter and greener the branches, until the most exquisite and complex form of "the bright consummate flower" and it doesn't stop there; for the flower "spirits odorous breathes" which might mean pollen and nectar, the very end products of the tree, which by their nature are vibrant, colorful, and paradoxically, as effervescent as they are evanescent. Yet the "purpose" of the tree, in its complex hierarchical structure, is to produce flowers and their fruits. And as it says, "ye shall know them by their fruits." So the meaning of the being of the tree is (revealed in) its most complex and beautiful product of the flower (and its fruit).

The botanically informed angel-quote continues from the plant realm and into the human one. But first, a step up from plants, are animals.

Man's nourishment, by gradual scale sublimed,

To vital spirits aspire, to animal

Now, there are several ways to interpret the first line here, but one of them is by taking man's nourishment to mean his food, and fruit is certainly a food. Man does not eat leaves or bark, but fruit is sublime. Is the flesh of animals even more sublime? One can also interpret this as implying a normative statement "man should" eat this and that, and not just a description of where he already gets is food. Yet we also have the more metaphorical one in which man should aspire to get his sustenance from more elevated sources still, that is, from the angelic, the spiritual, the contemplative. Yet to get back to the fruit; it is in the plant realm. "Its sphere assigned." Now we have what seems to be increasingly vital spirits, going "up" (from the word "aspire") to the animal realm.

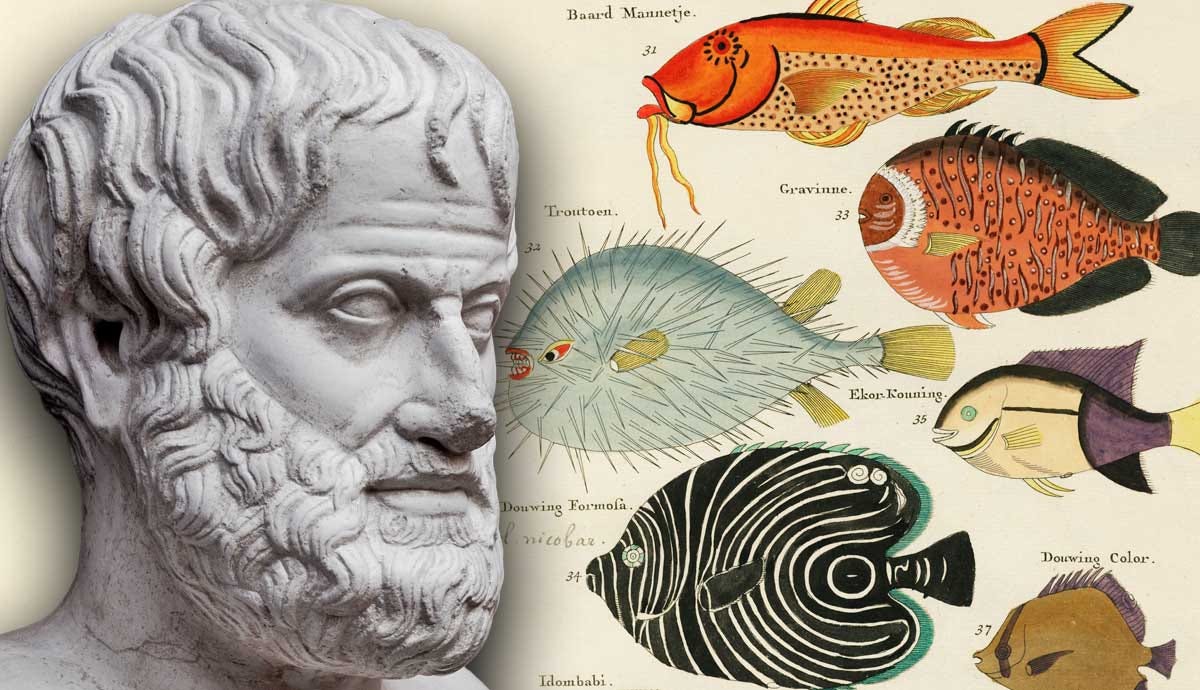

Here we can contemplate a major source of metaphysical world-building from the very man who introduced us to metaphysics as such - a vital think-font for the ancients, the medievals and now, after the renaissance, the early moderns - the Greek philosopher Aristotle. In his De Anima or "On the Soul" Aristotle lays forth his scheme for understanding the soul. In the ancient Greek world, soul was not a substance or "thing" inside you, nor was it "consciousness" or "thinking" and it most definitely was not an illusion of the mind, or a construction of culture. Of course, for the ancients, soul could be many things, but Aristotle helped to articulate as a philosopher, that soul was first and foremost "the form" of something. Soul is the form of the body. And there are many different bodies. The plant body has a certain shape, but its form is not its geometrical shape, but its vital force (Raphael talks of "vital spirits") its animating principle. Yes, animal comes from the ancient Greek word for the soul. Being animated, refers to people who a very lively, who have a lot of life or "spirit". And animation of course means making pictures or images move or "come alive." Mind you, this is not a dualism, since the soul simply is the form of the body, and the form of the body is the way of life of the organism, there is nothing inside the animal other than its organs and mode of being to account for its movements and life. No "hidden essence" or substance. Aristotle was somewhat of an early empiricist, being interested in classifying the living world via observation staying close to the phainomena (phenomena; "that which manifests itself, that which appears") As Raphael, Aristotle is classifying the souls of beings in a hierarchichal manner. First, we have the simply inorganic ("organ-less") which however elemental and endowed with ruling principles of their own, do not possess souls. These are things such as rocks, or phenomena such as flames, running water, clouds etc. Then we have plants. They belong to their own realm, and have what Aristotle called a "nutritive" soul. That means that their life-principle is fundamentally to absorb nutrients, develop and grow through cycle. Animals have a nutritive soul, as they also absorb nutrients and grow through cycles, yet they can also move, use their senses and communicate. They have a "sensitive soul." And here we come to the human.

To intellectual; give both life and sense,

Fancy and understanding; whence the soul

Reason receives, and reason is her being,

Raphael explains how Adam (and Eve and all the humans) have come up "to the intellectual" and is given both "life and sense". For Aristotle, humans are in possession of a nutritive soul (like the plant) of a nutritive and sensitive soul - like the animal - and an intellectual or "rational" one on top of the others. Importantly, for Aristotle it is not the case that we are a conglomeration of stacked souls, but whole organisms were all of the vital energies are united in harmony. We are not simply animals that have rational faculties stuffed into our heads with which we are forced to reason, but zoon logikon the rational/thinking animal.The most oft-quoted frace is "zoon politikon", "the political animal" but no politics without language! Raphael says that we are granted "Fancy and understanding" which hints at rationality not as this abstract ability which removes us from things, but rather places us more humanly in the midst of Creation through our own mode of being. We have the ability to speak, to think and to act on our own discernment. To separate, contemplate, and calculate; to "reckon" as Hobbes would have it. To allow our tabula rasae to be shaped by the impression of the world on our senses and develop our minds as Locke would have it. And reason, to get back to Aristotle is indeed as Raphael says "her being". Reason is the being of the soul, in other words! Yet as we have seen, reason is not a substance hidden within, not a cryptic substance or mysterious essence, but the very form the human life takes. It is part of our nature, not something super-added to it.

Discursive, or intuitive; discourse

Is oftest yours, the latter most is ours,

Raphael continues with an account of how the angels and humans are alike in rationality, but also slightly different. "Discursive, or intuitive" it would seem as if he is here stating that humans are more discursive, and angels more intuitive. If this is so, it makes sense. We are not as elevated as angels; not as privy to Gods complete design as our angelic cousins, yet we are rational. We are "political animals" our limited perspectives are actually a precondition for our communication, as our horizons of understanding can melt together in conversation. As such we are "discursive" using language as both a necessary limiting factor, and as a semantically opening field. Yet, through this activity, necessary and beautiful though it is, we are not as "intuitive as angels. They can "intuit" things, with their spiritual immediacy, the prowess of their more elevated souls and forms of understanding. Angels can presumably communicate more intuitively, more freely and more immediately with each other than we can. We are limited in our bodies, we speak in a flow bound by the temporality of the air that flows through our mouths, and in sex, two bodies join that must join in relative awkwardness and clumsily outpoured bodily fluids. Happy yet rare is the state in which the orgasm occurs simultaneously for the two parties involved! Yet, as is explained in another part, when angels have sex, they are somehow intermingling in another - to repeat - immediate way than us. Their bodies being of a different lightness and ability than ours ... yet, yet bodies they have none the less ... bodies they are! It is interesting that "light" as in "light as a feather!" and "light" as in "rays of light" are spelled exactly the same.

"Differing but in degree, of kind the same"

We have here in the above line perhaps received the biggest break in the rule of "show don't tell" as Raphael spells out that humans and angels are not actually different in kind, but in degree. This can, as I have attempted to show, account for not just humans and angels, but the world as such "the soul of the world" is its form, and its form is material. So everything can be accounted for via the same principles, even things like thinking, sex, reproduction, nutrient-consumption and even free will. Interestingly, Miltons "materialism" as we might call it, is not a bleak "determinism" where everything is mechanical and pre-determined as if we were wires and wheels bumping into one another. No, Miltons materialism is a dynamic and lively one. Perhaps his is a tad different from Hobbes then? It seems as though we have the ability to develop, grow and change. Change our form and thereby the shape our soul takes. We can become more like angels.

Time may come, when Men

With Angels may participate, and find

No inconvenient diet, nor too light fare;

And from these corporal nutriments perhaps

Your bodies may at last turn all to spirit,

So, the fact that we might end up finding "no inconvenient diet" nor "too light a fare" ("fare" here meaning good food served at a restaurant for instance) and participate with the angels, means that they not only have sex, but also eat. Angel food! One might wonder what that is like. What that is light. For it is not different in kind, but in degree. Angel food, angel sex, angel life, it seems simply lighter. Light as light. To us sluggish humans, it seems easier, quicker, more beautiful. Yet Raphael is hinting at a dynamics; a possible development; that we humans can aspire for something higher. Our very bodies might turn all to spirit. Which strangely, does not seem to imply that the angels are not embodied. I venture to say that in order to eat, drink, speak, move and have sex, you're gonna have to have a body with which to do these things. Yet their bodies are pure spirit. Again, we should think of spirit here as something material in the sense of something substantial; something that is observable, living and part of the rest of everything. And our bodies might turn "all to spirit" which, to follow up the botanical observations above, might mean that we are moving from the stem up into the leaves, and even all the way up to the flower.

Improved by tract of time, and, winged, ascend

Ethereal, as we; or may, at choice,

Here or in heavenly Paradises dwell;

At "choice" there we have the moral dimension, which has been in the background all the time.

Raphael continues:

If ye be found obedient, and retain

Unalterably firm his love entire,

Whose progeny you are

Here he says that there is a precondition for the aforementioned possible development into fairer states of being. And that is the obedience and unaltered retention of the entirety of the love to whose progeny we are that is the condition we must meet. We must be odedient to our Creator, through our love for him. A love he has freely given us by sending his only son to die for our sins. This is the New Testament, and in Book 2 of Paradise Lost, Jesus, the Son of Man is introduced as the supreme one of all the angels and forces, and he also freely, must make a choice.

Well hast thou taught the way that might direct

Our knowledge, and the scale of nature set

From center to circumference; whereon,

In contemplation of created things,

By steps we may ascend to God

This is Adams reply, grateful as he is for all this information. Yet pondering aspects still.

He reiterates the cosmology "from center to circumference" that everything is related and intertwined, yet also scaled, differentiated in placement and function, yet not in kind. And that we can, and perhaps indeed are encouraged to "ascend to God". But certain things baffle Adam.

But say,

What meant that caution joined,

If ye be found

Obedient?

Can we want obedience then

To him, or possibly his love desert,

Who formed us from the dust and placed us here

Full to the utmost measure of what bliss

Human desires can seek or apprehend?

Here the essential question of free will rears its serpent-like head. Adam, in what already can be called an act of free will in the very nature of his open question, asks how it is possible to not be obedient or desert the love of the one who created us. He - God - made us complete, content so in what way can we not obey? Can we break with our own nature? Is it in our nature to break with it? To break our union with our very creator? How can this be?

To whom the Angel: “Son of Heaven and Earth,

Attend! That thou art happy, owe to God;

That thou continuest such, owe to thyself

Raphael answers Adam, and says "yes, you are indeed made a certain way. You have a nature! But in what way does that make you believe that it is not also a part of your nature to rebel?" There is almost a certain existentialism to Raphaels words here. You are "thrown into the world" (Being-in-the-World) you have a "facticity" yet you still, and importantly, cannot choose not to act. This in itself would be an act! It is inauthentic to lean on your past, the "facts" that pertain to you, your "animal nature". For the existentialists, the importance of choice was highest, for we are the beings that are a problem unto ourselves. To get back from late modern philosophy to renaissance cosmology; Raphael is claiming that it is up to Adam to continue to be content, happy, or not to.

God made thee perfect, not immutable;

Adam is free in the sense that his life is his own, not somebody else's. Just as he is free to move, think and act, so he is free to veer of from the path of God. He is free to not ascend to the status of angelic being if so he chooses. As of yet he does not fully understand how this is possible, but it is.

By nature free, not over-ruled by fate

Inextricable, or strict necessity:

Indeed, it is Adam that does not understand that to be determined by previous causes, necessary principles of ion-clad laws is neither love nor freedom. The processes through which we are involved can be counted as open systems. This is not a deterministic universe, however material it is. As I said, this is a dynamic world of spirits and forces, forms changing into forms but never escaping the world.

Our voluntary service he requires,

Not our necessitated; such with him

It is part of Gods very plan, from the smallest rock, to the highest angel, that we should choose Him. Freely. If he created humans to serve him unquestioningly, blindly, instinctively, he would have. But he wanted us to choose. We humans create machines to serve us and our ends, yet we know - no matter how much we speak to the AI-voice - in our hearts that the machines do not choose anything; neither to serve us, love us or communicate with us. In fact, communication, as I have touched upon, implies another; another soul, self, mind. And God did not create us as machines, but as living creatures open to the world, to Creation, being ourselves part of ut.

Raphael asks:

[How] Can hearts, not free, be tried whether they serve

Willing or no, who will but what they must

By destiny, and can no other choose?

To choose because you be necessity must, is not to choose. Even to go against your own contentedness and health is something you can do. Even ... to fall!

What about the angels then?

Myself, and all the angelic host, that stand

In sight of God, enthroned, our happy state

Hold, as you yours, while our obedience holds;

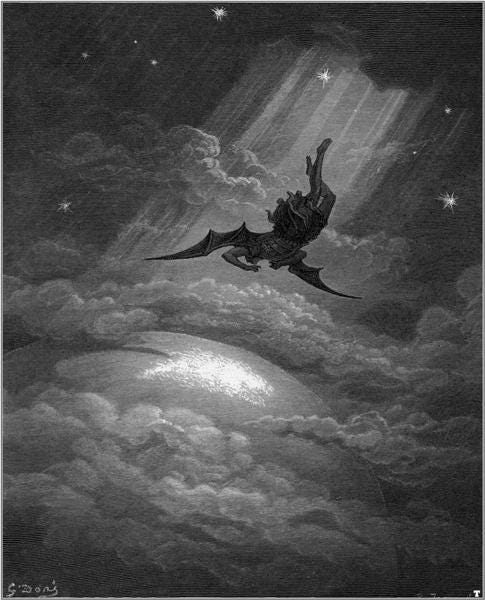

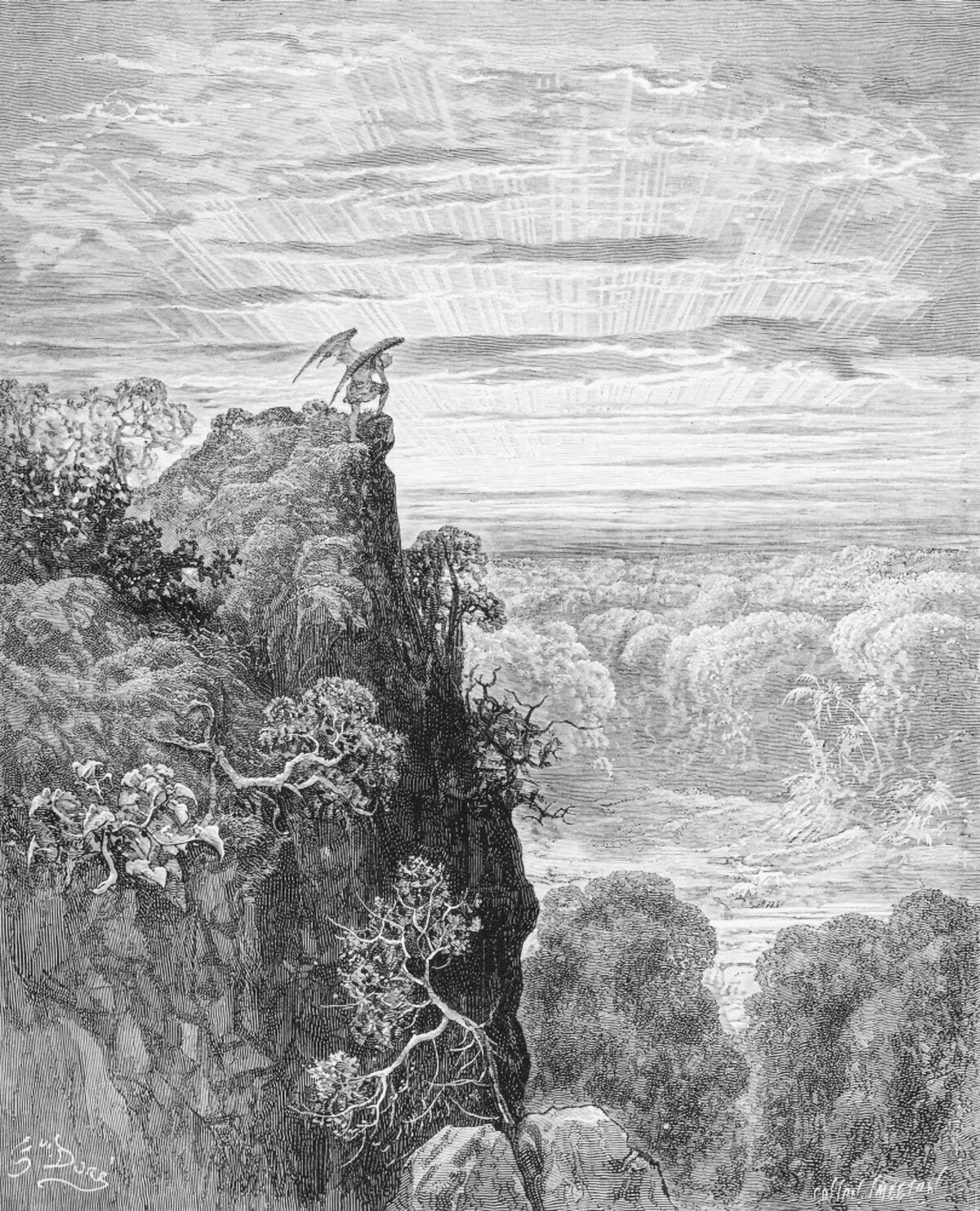

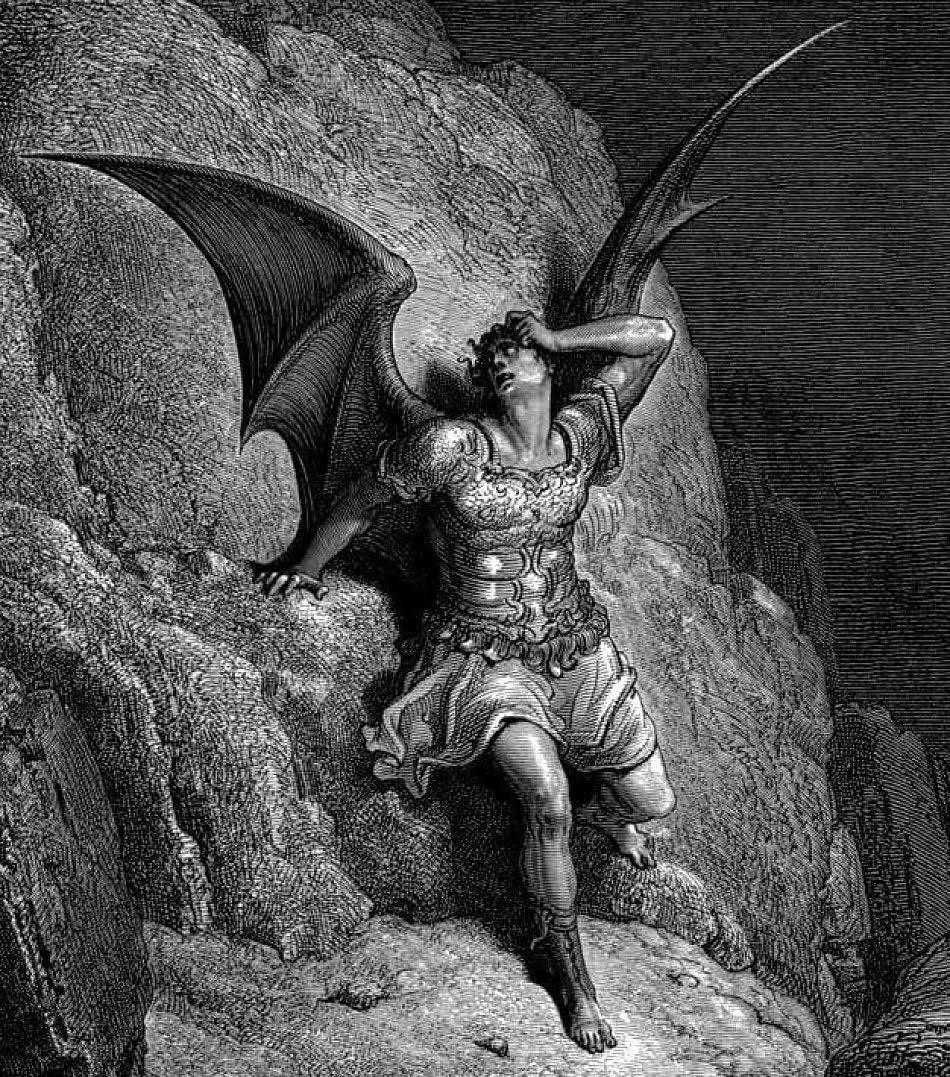

The angels seem here to choose continuously to stand with God, to choose to obey God in happiness, rather than disobey in fallen-ness. Indeed, who was the first that really fell? It was the great rebel, Satan! The very first pages of Paradise Lost, describes not the fall of Man, but the fall of an Angel, indeed not just an angel, but the supreme angel. Satan had to first survive the new realm into which he and his host was flung, then build a Pandemonium, then concoct a plan, and then, only then traverse various realms, Chaos, Heaven, Paradise, in order to arrive at the realm where he could seduce us. And maybe test our free will more than any other thought? The point is that angels also choose, angels are also material-spiritual as we are spiritual-material.

On other surety none: Freely we serve,

Because we freely love, as in our will

To love or not; in this we stand or fall:

And some are fallen, to disobedience fallen,

And so from Heaven to deepest Hell;

O fallFrom what high state of bliss, into what woe!”